When Will you Be in Crete Again?

[Written by CYA Spring’24 student, Jessica Wu]

“May the flowers grow old,

And may you like the wind of the sea,

For eternity, you merged into this most envied landscape,

Music of passion, recitations of heroes and gods, lies or truths about glory, and sad songs for the world beneath,

Lives, so early taken or given away, ever lacking a fruit or a trial…”

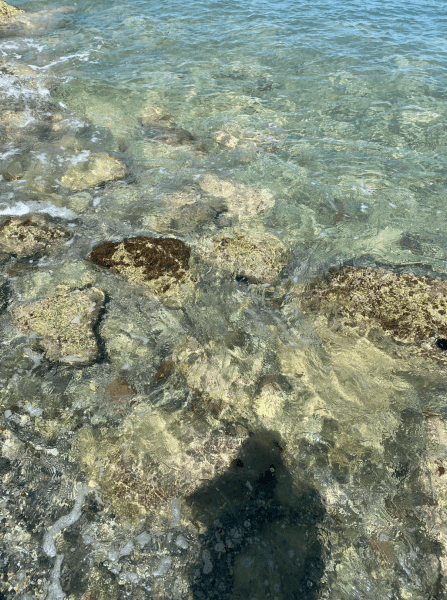

The sea at Plaka.

When we arrived at Souda to visit the WWII Allies cemetery, a boy was riding a hoverboard back and forth on the straight paved walking path. A simple large cross stood in the middle of the lawn. All tombstones face the bay, looking over the much-loved and praised Aegean sea. Flowers grew before the gravestones, in front of the names (or, many identities are unknown). As the Greek fighters who died in the resistance would be buried in their own communities, the cemetery here is exclusively a resting place for foreigners.

One generation after WWII, young people in Europe and America would “discover” the Greek sun, sea, food, and nature, as an alternative world from the one of national and collective struggles. Thus begun tourism in Greece as we know it today. As for the generation who participated in WWII, they may have heard the echoes of Zeus and his victim Europa. They may have thought of the youthful Athenian Prince Theseus who came to Crete in a band of human tributes and left as a hero. They may have recalled the aged King Eageus, after seeing the black sail, jumping into the water, as clean as crystal, dark blue as wine. Maybe some of them were readers of The Times, which followed the reports and updates from the British archaeologists about the excavations in Crete.

“Those flowers, who planted them?” I approached Professor Kritsotakis, whom I simultaneously respect and am afraid of. I wanted to ask something else about the names. But when the question was pronounced, it concerned only the blooming decorations.

How many of them might have liked literature, classics, archaeology, mythology, and history? I wanted to ask, knowing no one could have the answer. How many of them had wished to visit Crete as a pilgrim? How many of them might have dreamed of facing the most beautiful water, hearing story-telling waves, inscribing their names on monuments, and entering history as heroes?

Just not like this.

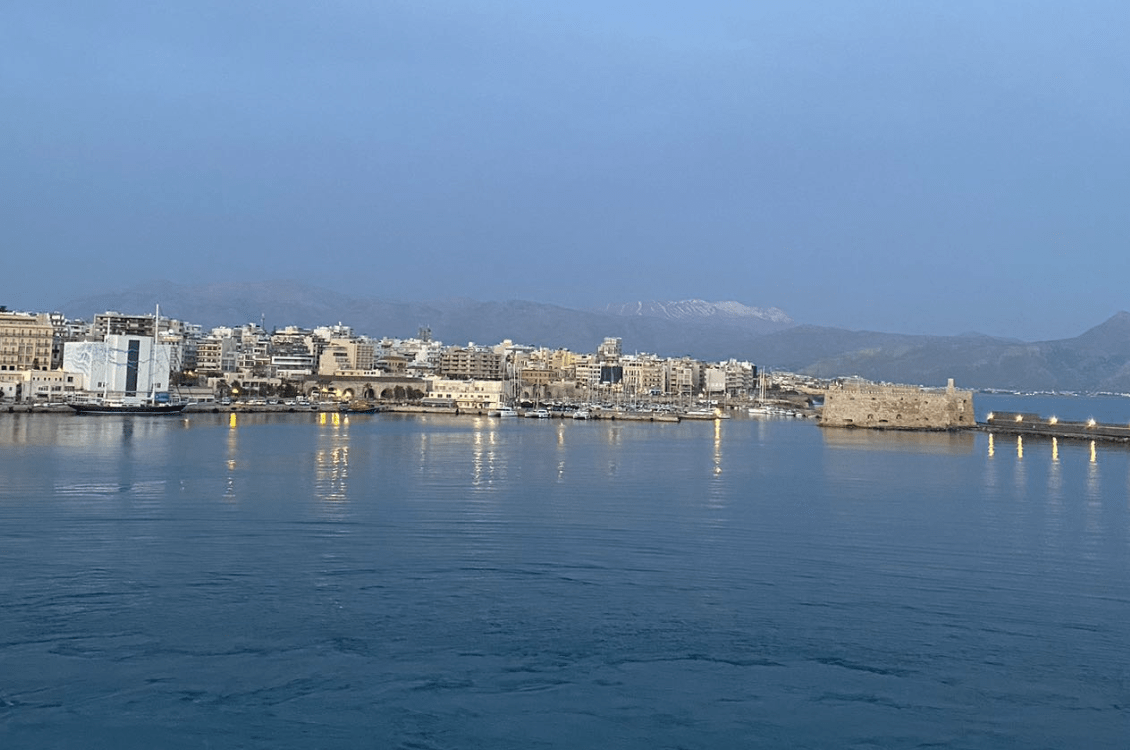

The sea from Heraclion

I didn’t finish my poem.

Before I could finish, we were already flying from Chania to Athens. I know why I started the poem in the first place: no matter how inappropriate, I have to settle my Cretan trip into words, into a narrative, into that painted reconstruction of memory, because time is merciless like an earthquake, and I don’t know when will I be in Crete again.

“Get into the water!” I remember friends shouting at each other on a windy day. We were in Plaka after lunch. The beach was rocky. Walking on it with bare feet was already a challenge. The wind stirred up the water; waves were touching my nerves. The water was somehow chilling, and I didn’t want to make a dive. Then I heard someone saying, not toward me, “When will you be in Crete again?” I took this as a sign. So, laughing, screaming, and almost crying, I made myself swim until I got used to the water temperature;

Taken by Angela Escalante

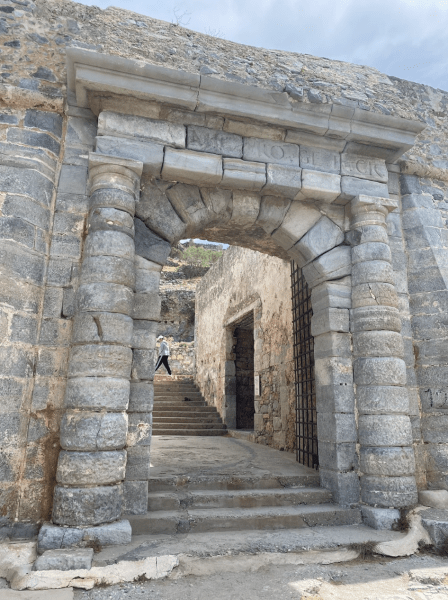

That morning we were at Spinalonga, a site where all buildings date back to the Ottoman occupation. Back in history, it was a colony of people with leprosy and their families. Isolated forever on this islet, the inhabitants built their own independent community. History should be honored. Yet no one discouraged visitors from remarking on the beauty of peaceful ruins. In front of the entrance of the village, people were waiting to take pictures of the open dock through the old gate of rock when no one was in view.

The memorialized village was on one side of the island. The other side was a long path. I wandered on that road by mistake. Once on the way, I heard the sea breathing below the shore; I looked around at the trees so outstanding from the endless blue sky. The bright and aggressive sunbeam dried the lonely road. Later when I met a few friends who were also on this path, I recalled in a clear memory a dream I had years ago. The dream was made long before I knew that my undergraduate major would come to be classics, not to mention a study abroad semester in Greece.

This road appeared there in my dream. Several friends I’ve never met appeared in my dream. The sound of the same wind appeared in my dream. The lonely feeling, as if walking in a desert, also appeared in my dream.

This road appeared there in my dream. Several friends I’ve never met appeared in my dream. The sound of the same wind appeared in my dream. The lonely feeling, as if walking in a desert, also appeared in my dream.

History should be honored. I stood at the original gate of the islet and warned myself against self-indulgence again and again. Not so long ago, relatives and friends of the patients would meet the inhabitants there. With a space separating them, they would be talking and looking at each other, yet they could never shake hands, or hug, or kiss. “Forgive me for thinking about my own dreams.” I untied my hair to feel the wind. Standing at the old dock for a long silence, I left myself behind the group, “but I don’t know when will I be in Crete again.”

History should be honored. I stood at the original gate of the islet and warned myself against self-indulgence again and again. Not so long ago, relatives and friends of the patients would meet the inhabitants there. With a space separating them, they would be talking and looking at each other, yet they could never shake hands, or hug, or kiss. “Forgive me for thinking about my own dreams.” I untied my hair to feel the wind. Standing at the old dock for a long silence, I left myself behind the group, “but I don’t know when will I be in Crete again.”

“I’m going to Crete this weekend with CYA!”

“I’m going to Crete this weekend with CYA!”

“Are you going to Knossos?”

“Yes.”

“May I remind you that I’ve written a book about Sir Arthur Evans and Knossos?”

“Yes, I’m reading your book!”

It took a while for me to realize that the professor who wanted to present Thucydides’ history as a novel at the workshop was a leading authority on Minoan civilization. It took even longer for me to realize that the “legend in archaeology, classics, even in Greece broadly speaking,” according to three Greeks whom I know, was a lovable author.

It took a while for me to realize that the professor who wanted to present Thucydides’ history as a novel at the workshop was a leading authority on Minoan civilization. It took even longer for me to realize that the “legend in archaeology, classics, even in Greece broadly speaking,” according to three Greeks whom I know, was a lovable author.

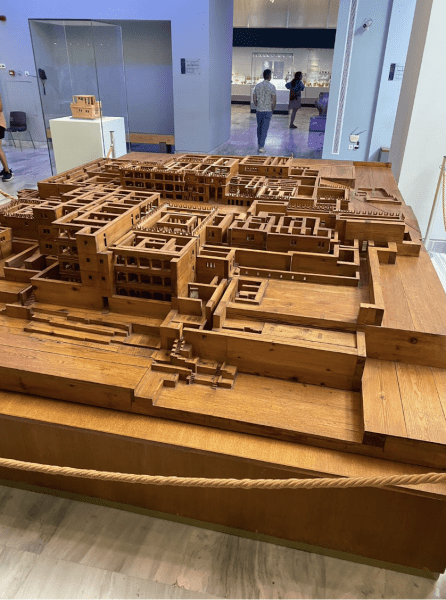

In the cabin of Minoan Line, by the reading light, I read about how Arthur Evans’ reconstruction of Knossos was received by the public – not according to his expectations. Today’s archaeologists don’t adore him let’s say, because his reconstruction was a violation of principles. But the visitors back then made different judgments, aesthetic ones, such as the throne room was not bright and large enough to befit a civilized ruler. Or, being misinformed, they were disappointed in the fact that the whole visible structure was a reconstruction, even an archaeologist’s “fantasy.”

“And Evans’ Greek colleague was writing to argue with that tourist. He says that man should have asked an archaeologist to guide him.” I handed the book to a friend, joking about the previous visitors who were not satisfied by the so-called Palace of Minos at Knossos, while the boat was carrying us to the same town. We laughed. Then I suddenly had a thought that made me lost for words. I gazed at my bookmark which the professor signed for me at our last workshop session. Because the last session was over, I will not be able to report my Non-disappointment at the Palace to her in person again.

“And Evans’ Greek colleague was writing to argue with that tourist. He says that man should have asked an archaeologist to guide him.” I handed the book to a friend, joking about the previous visitors who were not satisfied by the so-called Palace of Minos at Knossos, while the boat was carrying us to the same town. We laughed. Then I suddenly had a thought that made me lost for words. I gazed at my bookmark which the professor signed for me at our last workshop session. Because the last session was over, I will not be able to report my Non-disappointment at the Palace to her in person again.

Villa Ariadne, Sir Arthur Evans’ residence in Knossos

Villa Ariadne, Sir Arthur Evans’ residence in Knossos

The next morning we arrived at Crete. At that moment I still thought three days were long enough for the island. When we entered the palace, I was energetic enough to imagine her voice, through her words in her book, disagreeing with my professor. Whenever Prof Kritsotakis said the reconstruction was beyond necessity, I recalled the book talking about Evans’ desire to represent the aesthetic of his beloved civilization; whenever Prof Kritsotakis said about how arbitrary some artistic interpretations were, I recalled the book stating that Evans’ colleagues used to testify his expert knowledge and his scientific spirit; whenever Prof Kritsotakis pointed out the material for reconstruction didn’t exist at the time of the Minoans, I recalled the book talking about that concrete was used because there were two earthquakes during the process.

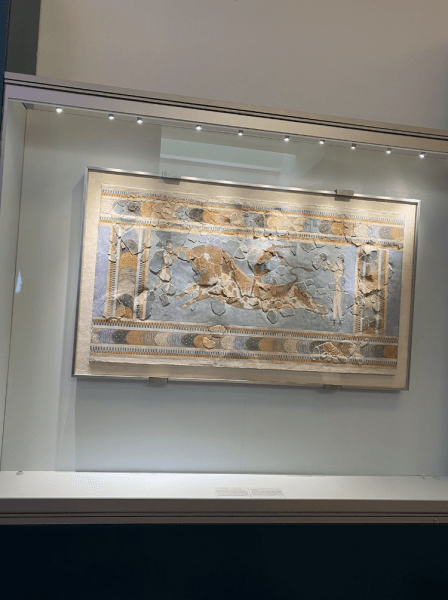

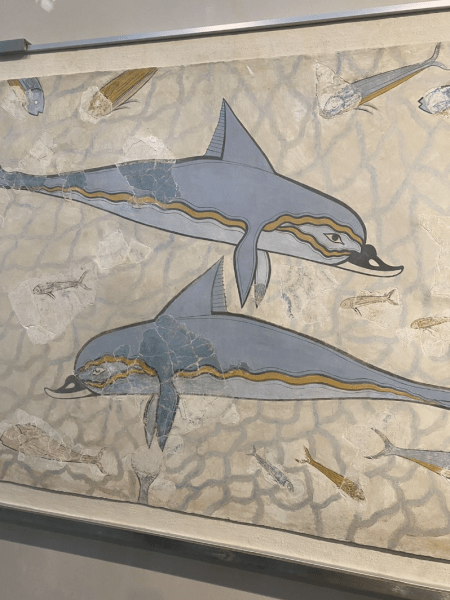

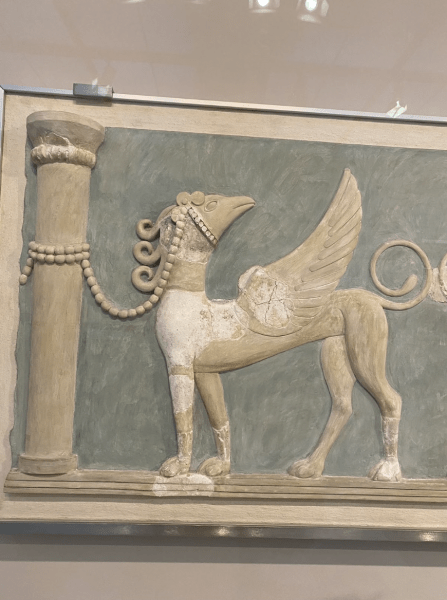

The model of the Knossos Palace, Archaeological Museum of Heraklion

Archaeological Museum of Heraklion

Archaeological Museum of Heraklion.

Peacocks were walking freely on the site, with their majestic gestures, as if the palace was theirs. After the on-site lecture, a few of us stepped on some stairs to go behind a building. When no authority but the birds were around, I confessed to my friends, “Actually I’m reading a book written by the daughter of one of Evans’ Greek colleagues here, she herself is an authority in the field. She has fewer issues with Evans. She likes him. She even named her cat Arthur.” I looked around and saw my professor engaging in a conversation far away, “I will go with her opinion because she is nicer to me than Kristotakis.”

So we like concrete.

So we laughed.

At that moment, I was missing her voice, which I can hear only on YouTube now. The more our librarian told me that my bookmark with her name was precious, the more I realized that even though she is alive and healthy and I can revisit Greece, I could never be good enough to enter her world. On the other hand, my professor was there. If I just walked down the stairs with a question, I could approach him easily. Not until the end of the Creten trip, until all the voices but the flow of vehicles in Athens had ceased, until that normal evening when I said “See you tomorrow,” until the next Monday I found myself being as behind as usual in Ancient Greek class, I realized that I was unfair.

Taken by Sam Sidders. At Heraclion. Professor Demetrios Kritsotakis on the left, and me on the right. This article is written near the end of my CYA semester. If it’s allowed, I wish to store this one memory on the internet as Prof Kritsotakis is a professor whom I quite admire.

(Taken by Sam Sidders. At Heraclion. Professor Demetrios Kritsotakis on the left, me on the right. This article is written near the end of my CYA semester. If it’s allowed, I wish to store this one memory on the internet as Prof Kritsotakis is a professor whom I quite admire.)

When is my next time in Crete?

When is my next time in Athens?

Will I ever be good enough to see you again, to hear your voice again, in your world?

Or am I, eventually, a self-indulgent tourist who only keeps the glooming sun and sea in memory of my youth?

Taken on the boat, on the way to Crete from Athens