From “Greased Lightning” to Greece Enlightening

by GLYNIS BRAUN (CYA Spring 17′)

I remember that my parents were not thrilled with the idea of my sister and her new husband honeymooning in Greece in August of 2015. No less than a year later, I then told them I planned to spend a semester studying here in Athens. Their reaction was the same.

Although they would be worried no matter where I chose to study abroad, they were even less pleased with my choice to head to a country in a crisis. They were not the only ones with this reaction. While about half of the people I told would “oooh” and mention something about the beautiful islands, the other half would say something like, “Greece? Why would you ever want to go there?” This was insulting to me because I clearly had done my research about the program and country before deciding to spend four months of my life there. If this comment bothered me, I can’t imagine how much it would insult a person of Greek nationality.

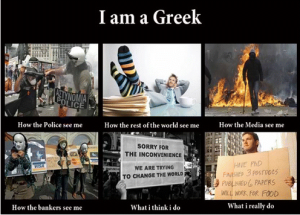

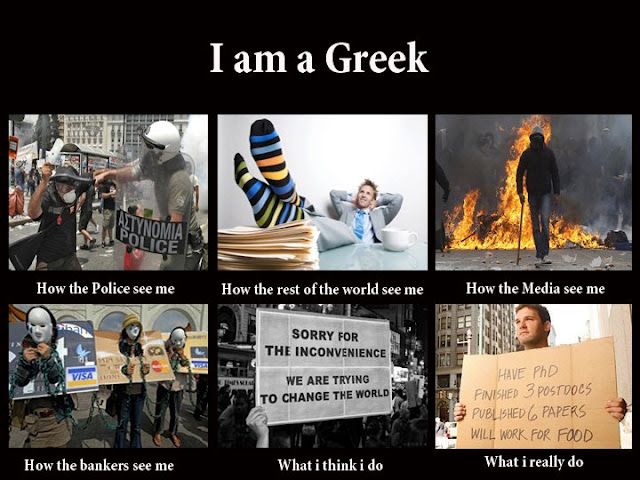

Stereotypes are defined as “a belief, usually negative, about a group of people regardless of previous interaction.” My parents, friends, and others who had never been to Greece before, during, or after the crisis were making judgments about Greeks and Greece without any type of justification or real experience. After an event like a crisis or attack, stereotypes are intensified and even more damaging. For instance, Muslims in the United States in the aftermath of 9/11 were discriminated against and stereotyped more regardless of their personality, beliefs, or background. This is a similar case for the Greeks after the crisis. People base their judgments of others on what they see, read, and hear in the media, commonly without checking their sources or facts. Likewise, the Greek crisis happened during a time where the Internet was beginning to explode with social media activity, thus many people got their information- both true and false- here.

In a study called “Small Stories of the Greek Crisis on Facebook,” one doctoral student studied the posts of her Greek Facebook friends during the crisis. She randomly selected five Greek Facebook users and her plan was to monitor their activity online surrounding the crisis. She believed that this would show how the “the economic and socio-political turnaround in Greece dominated the lives, and concomitantly the content of Facebook posts, of the people I was studying.” However, in her methods she notified the five participants and told them what she was doing, thus they were aware that their posts were being monitored for anything related to the crisis.

This could have been an interesting study, but since the participants knew what they were being watched for they had the incentive to post about the crisis. This is referred to in sociology as the social desirability response bias, which is when participants of a study will give answers or perform actions that they think researchers are looking for or are acceptable.

Although this study was a bust, (in my opinion), it shows how Facebook can serve as a public diary. Greeks could express their struggles and complaints freely to their Facebook friends. Additionally, their audience was not just Greek people going through similar things, but also their friends from around the world. This way, people of all nationalities were getting a glimpse of the Greek crisis from their screens at home. The problem with this, however, is that one person or even five people’s stories do not represent an entire nation’s sentiments. Maybe your one Greek friend on Facebook lives in a part of Greece that was devastated exceptionally hard or is politically invested.

This is similar to people who write reviews on sites like TripAdvisor and Yelp- usually, the people who write reviews have strong enough feelings to leave a comment, while those who are satisfied or apathetic do not. Not all people will post about their lives, therefore Facebook is not representative of the entire Greek population. Furthermore, Facebook is still an exclusive social media site, with most of its users being younger and educated, which not all Greeks are.

While one would expect a social media site like Facebook to not be the best source for information (though some people sadly do) sometimes the news we receive on television and in print is just as biased. For instance, how the US portrayed the Greek crisis in its reports and analyses influenced how average Americans saw the crisis as well. One source says that “by drawing attention to dramatic events in Athens and the American stock markets, US outlets presented the financial crisis in narrow terms that blamed the event on alleged character flaws and ineptitudes of a nation and its people.”

Thus, the American news outlets were not offering sympathy for the Greeks, instead, they were blaming them for the situation they were in. This is partly because Americans are so obsessed with the American Dream mentality and that hard work will get you anywhere, regardless of your situation. What American people were seeing on the news versus reading on their Facebook timelines from their Greek friends probably differed drastically: the former blamed the entire nation, and the latter blamed its government.

Before coming to Greece, I had never been to Europe before. The main stereotypes I had been exposed to of Europeans, in general, was that 1) they dress well and 2) they don’t work. I had heard from multiple people that Europeans were lazy and just sat around all day drinking coffee and smoking. My dad even joked with me before I left that if I stayed in Greece I wouldn’t have to worry about a job search after college. Because of these stereotypes, it is not surprising that when Greece went into crisis many Americans saw their “laziness” as the problem, and even saw them deserving of such a crisis. Had they just worked hard enough, people thought, perhaps they wouldn’t be in such debt.

Now that I have been in Greece for almost an entire semester, I have a different perspective to share with my friends and family when I go home. I can tell them that even if they have Greek friends on Facebook ranting, most Greeks (or at least the ones I have encountered) are not visibly angry or depressed. In fact, Greeks are exceptionally more happy and friendly than Americans! Likewise, there are just as many homeless people in Philadelphia, my hometown, as there are in Athens.

As far as laziness goes, there is a different mentality here. Sure, old men like to sit all day in coffee shops, but they also run their own stores, tavernas, and such, working long hours and with little staff.

So, when I return to the US and tell people I studied abroad in Greece and they ask, “Greece? Why did you want to study there?” I can give them a whole list of reasons why, and hopefully change their perspective. In the 1978 movie, “Grease” starring John Travolta and Olivia Newton-John, one of the catchy show tunes is called “Greased Lightning”. I like to think of my semester here as a play on that, as “Greece Enlightening” because I have learned so much about a country I knew nothing about, and formed my own opinions regardless of what others “warned” me about back home.

Source

Written by Glynis Braun for her class CO346 Mediating the Message: Social Media and People (in Greece) 20/4/17 (full references provided)