Peloponnese Under the Sun – A CYA Student’s Reflections

[Article written by CYA Student Jessika Wu. Photos by CYA student Chloe Revier]

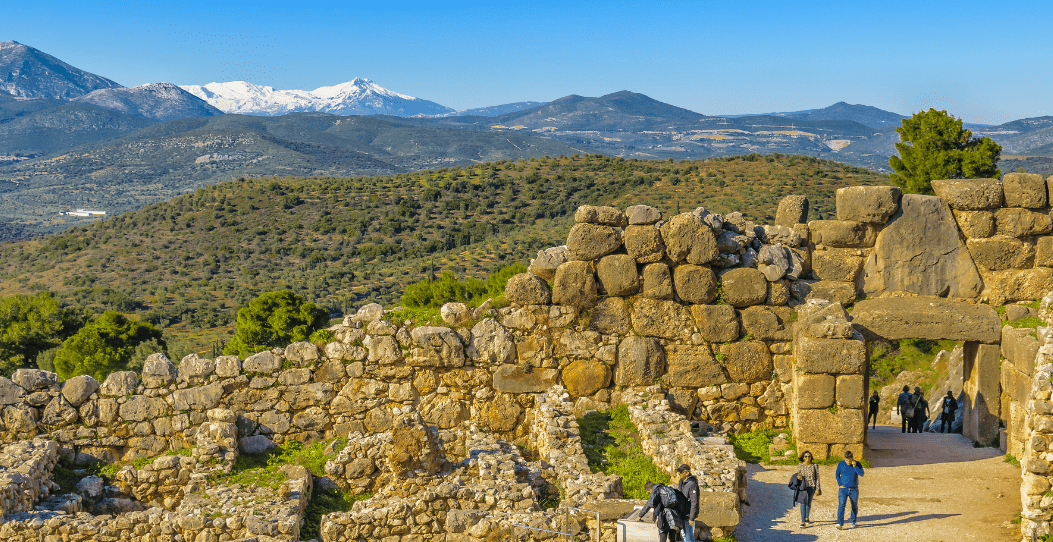

Mycenae

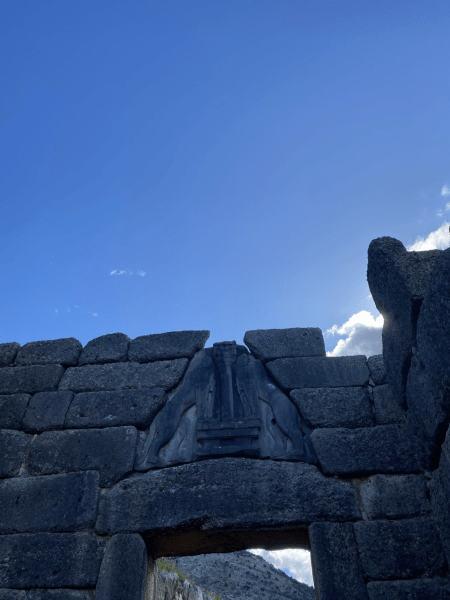

The site is an ancient citadel, fortified with stone walls, occupying a strategically advanced stop. It was a site suitable for wars. But the ruin is peaceful. We walked the way uphill to reach the Lion Gate. Beside the paths, wildflowers are blooming on the hill covered with fresh-green grass. Spring has arrived. The wind was chilly but the sun molified the coldness. The perfect weather under this part of the sky indicates a kind of generous hospitality.

I experienced an encounter with the Ancient, and remarks by knowledgeable people, about Bronze Age civilizations. For example, they say, the economic system must have been a centralized one: see the grain storage inside the walls, beside Grave Circle A. They say a visitor can recall warriors associated with here, the legendary Agamemnon, son of Atreus, king of the Achaeans, lord of the people, etc, being one of them. They say, pay attention to the Megaron, where the king stayed; they say, gaze at the place for hearth, where the household and the community are gathered and consolidated by the flame. Look around, imagine the sailers going to the sea; see the mountains, or think about the limestones and the building structure. Just think of history. Back in their time, potteries from Mycenae were traded far across the sea. The museum is exhibiting some seal stones used to sign those potteries. It’s easy to envision an inter-continental network.

Trading goods, those ancient lucky travelers who got to see the world. Now, many more people can. Besides us, another group was holding an on-site lecture. They were speaking German. I also heard another three people, seeking a good spot to take pictures, conversing in my native tongue. I speak Chinese. They were probably a family on vacation. One of them who knows English was trying to translate the descriptions in front of the site for another. The period for celebrating the Lunar New Year hasn’t ended yet. Suddenly, I turned from my group, the palace, and my professor, and I glimpsed at them. “Tourists only know about taking pictures and buying olive oil.” I thought negligently. But I desired, for that one moment to say some words of greeting or good wishes.

However, only I was romanticizing, I only shared one word with them;

“Careful!” I shouted to the person sitting on a rock, in a language ever foreign to these mountains, to this sky. We walked down the hill in silence, side by side, along the same road that led us to the Lion Gate, overlooked by the Mycenean fortification. Spring has come. Yellow wildflowers are blooming. Then we, strangers, without exchanging even one word, separated, they to their next station, and I to my group.

2.14, Saint Valentine’s Day

Love-heart stickers were put on the windows all over the bus. The itinerary includes two museums, one for water power, and one for traditional Greek costumes. I have very poor vision (so it was very difficult to read any description on site) and poor background knowledge about both water mills and traditional Greek costumes, so I can’t report much other than the nature, the water, and the Collection of Greek Costumes’s delicate arrangement for exhibition. But in general, this day offered us an alternative impression about Greece. The sea, beach and white-painted walls are features of the Cyclades Islands, not all of Greece. My extbooks remind me that Greece is mountainous, and our trip through the Peloponnese intensified this understanding.

The water power museum is connected to a network of hiking trails going deep into the mountain. Next to the museum is Dimitsana, a beautiful town with rock houses covered by red tiles. It’s built on the mountain. Layer by layer, roads and houses were displayed there, almost independent of its pure-green background and the outside world. Later in Kalamata, standing beside the sea, gazing at the sunset, I flew my mind back to that small town in the mountains. A few friends were also there, and I was thinking about how to write my article.

The water power museum is connected to a network of hiking trails going deep into the mountain. Next to the museum is Dimitsana, a beautiful town with rock houses covered by red tiles. It’s built on the mountain. Layer by layer, roads and houses were displayed there, almost independent of its pure-green background and the outside world. Later in Kalamata, standing beside the sea, gazing at the sunset, I flew my mind back to that small town in the mountains. A few friends were also there, and I was thinking about how to write my article.

“How to describe the town that we visited earlier, other than using ‘beautiful’ and ‘pretty’?” I asked for their wisdom.

“Majestic, Benevolent?”

Why not?

“Warn, because of the fireplace everywhere. ”

Indeed.

“Almost like a fairytale.”

It reminds me also of some animated cartons I loved back in childhood.

“Other-worldly.”

Meaning: too good to be real.

“Quint.”

I asked, “How to spell and what does it mean?”

“It’s like when your 19th-century mon walked into a medieval lady’s house and said, instead of ‘cute.’”

I learned new vocab then.

I remember what one of our professors said on the bus earlier: the idyllic mountain village character is maintained for tourism; in the mountains, alternative tourism from the islands and the big archeological sites is growing. Therefore, think of sustainable tourism and topics like that. Yet, in front of me are still mountains, sea, tides, and winds. A few minutes later, the setting sun shined through clouds and brightened the top slice of a nearby hill. Above the seawater, the light was as intense as burning. It colored us and everything around us into an oil painting.

Tastes

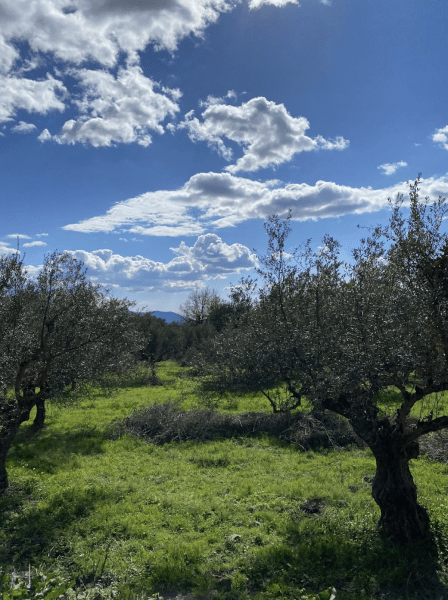

Olive is part of the culture, far more important than economic produce.

At Kalamata, the owner of an olive oil press shared his romantic rhetoric with his tourist group. “We don’t call it a farm. We call it the olive tree forest.” Growing an olive tree takes time and profits are small, so the trees were not planted by this generation. The trees have been there for a long time, people come and go, collecting olives, and making a living from their inherited forest. Most people in the area own some piece of land that grows olive trees. The olive production here is not industrialized. The lands were kept in fragments, in individuals’ hands. When we heard those descriptions, we were standing under the shade of an old olive tree. Its branches spread in four directions. Beneath it, a variety of herbs were flourishing. That tree aged over 200 years.

It was a story of land, of time, of people and nature, of the agricultural tradition of the area. It could also be a story going far back, till the days when shepherds, like those in the Hellenistic novels, would sit under one of those old olive trees to rest a moment. We sat down in the factory later for lunch. Bread, cheese, meat, even chocolate were dipped into olive oil. We also tasted the oil itself, learning how to tell the difference between oils of different quality. Olive oil had a strong flavor, it was bitter, and the color was dark green. From my companions’ excitement, I could tell their enjoyment. Yet sensation varies from person to person. Taking a salted olive in my mouth, I looked around, behaving cheerfully, while swallowing it like swallowing down some renounced literature from the canon.

The next station was an ouzo distillery in the city. We arrived at Nafplio, the first capital after Greek Independence. The distillery is a family-owned business. The telling of the distillery’s development was interwoven with the story of the old capital. We were lectured on history and on ouzo making. We were offered alcohol to taste. I took one cup of ouzo, and two small cups of brandy mixed with different flavors. Now, in front of the hall’s gate, our great bus driver opened the bus door and played drinking music from the bus radio. People got excited. My professor held a bottle in his hands and started pouring a little bit of brandy for everyone to taste.

On our bus ride from Kalamata to Nafplio, I had an opportunity to sit next to our Anthropology professor on the bus. She talked about the farmers turning to tourism for income besides their produce. She also talked about the agricultural labor situation in Greece nowadays. I was thinking about those critical topics on the bus. I even wrote down an NGO’s name: Generation 2.0. It’s okay to think critically while still enjoying the romantic, she told me.

I was imagining myself writing a delicate piece of work that would throw the reader back and forth between the romantic side and the critical side. It would be a non-fiction report and poetry simultaneously. But later, I got distracted by having a good time with friends. Eventually, that conversation with my professor left only one sentence in my writing: according to the Greek stereotype, American young tourists easily get happy in a silly way. I leaned on my friend’s shoulder and was very happy because of the sensational joy. Life seemed beautiful under the sun. Then, I wrote no more.