FALL SEMESTER

Enjoy the countryside and take advantage of much quieter beaches and inexpensive travel opportunities within Greece in the off-peak season. September's monthly temperature floats around 30C/86F, making ideal for swimming and island hopping.

READ MOREWINTER SESSION

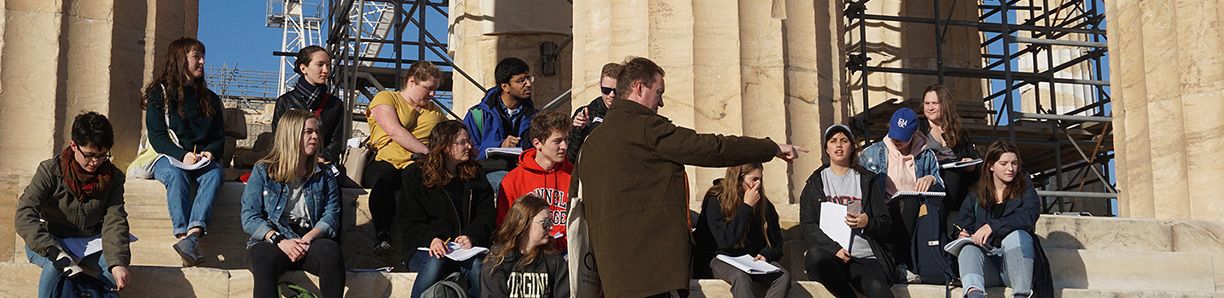

If you have a keen interest in archaeology or anthropology, you may gain experience and credit by participating in one of CYA's three-week Winter Intersession programs. Immerse yourself in a fascinating course within and about the city of Athens

READ MORESPRING SEMESTER

The countryside is filled with the colors and sweet scents of blossoms. The entire population seems to be out celebrating and enjoying not only the fine weather but also all holidays occurring in spring. First there are weeks of Carnival festivities in March

READ MORESUMMER SESSION

Summer is an exceptional time to study in Greece with a choice of unique CYA courses tailored to combine academics with authentic experiences, taking advantage of the sun, the sea and the vibrant summer culture from Athens to the surrounding islands.

READ MORE

APPLY FOR SUMMER 2025

Students interested in short-term, intensive study abroad are invited to our summer program in Greece, which combines academics with authentic experiences. Enjoy unique CYA courses that explore Greece’s rich history, engage in archaeological excavations, and delve into the anthropology of food, all while experiencing the vibrant summer culture from Athens to the islands.

BROWSE OUR OFFERINGS HERE

RENEW & RISE: CLIMATE ACTION AND FAIR ENERGY POLICIES

This summer course focuses on a comprehensive approach to tackling climate change and promoting equitable energy policies.

READ MORE

POSTBACCALAUREATE IN CLASSICS

Our Postbaccalaureate Program is designed to help college graduates improve their engagement with scholarship as well as their classical language skills, and take courses that prepare them for admission to graduate programs in Classics or Archaeology.

READ MOREUpcoming Events

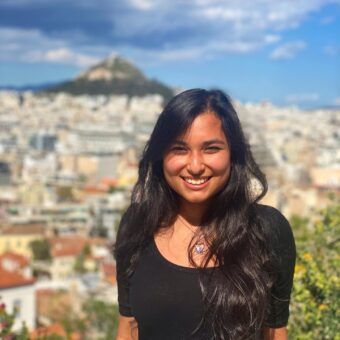

THE CYA EXPERIENCE

Active Professors in US, Canada are CYA Alumni

+

Average number of Athenian cats petted by each CYA student

Gyros consumed by CYA students per semester

Universities represented

+

Days of sunshine in Athens per year

+